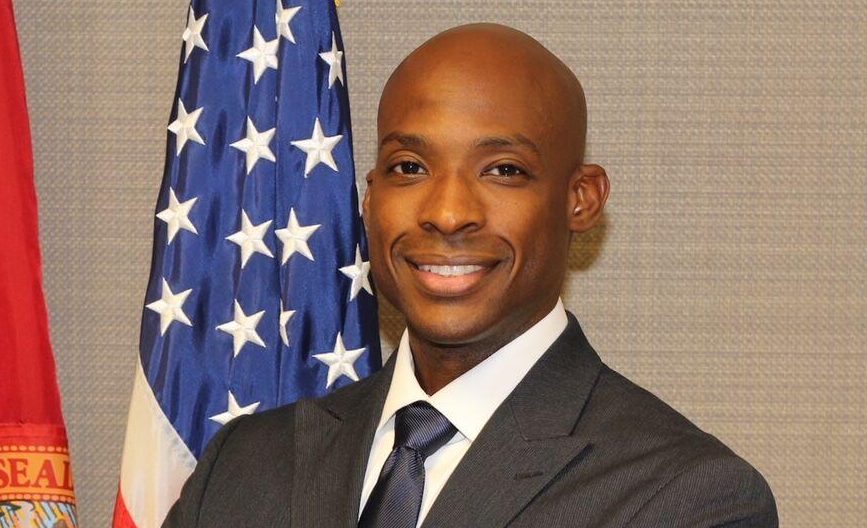

Journalist turned county employee Jason Smith always had a desire to see his community thrive.

He yearned for equity long before his young mind could comprehend the meaning of the word or the work required to make it happen. But slowly and surely, he worked his way up the social justice ladder – and today he’s the director of Miami-Dade County’s office of equity and inclusion, a position that gives him the ability to make real change.

Smith’s days are spent in meetings and helping to rewrite contracts to allow thousands, if not millions, of dollars to be directed toward the county’s small businesses. A primary goal, he says, is to take small steps in supporting equity by making sure the county’s budget reflects the community’s needs and long-standing issues.

So far, that’s looked like securing funding for the Historic Hampton House, mental health research and COVID-19 relief, and reinvesting in the Miami-Dade Economic Advocacy Trust (MDEAT), an agency initially established after the Arthur McDuffie riots that had been disinvested in for years.

Smith’s passion was first fed by a sense of community responsibility imposed on him by his parents when he was growing up in Richmond Heights, a community developed to provide affordable housing opportunities for Black veterans returning from World War II during the Jim Crow era.

“My dad would tell me the history of the community,” said Smith, “and that not only gave me a sense of place, but a sense that I had a role to play in keeping that history alive and contributing in some small way to the success of it.”

At 16 years old, Smith joined his father for the Million Man March in Washington, D.C., where more than 200,000 Black men gathered in protest of economic and social injustice powered by racism.

“It was life-changing and solidified my desire to give back to my family and community, and to be the best Black man that I could be,” Smith has said, calling the experience his initiation into manhood.

Two years later he graduated from Miami Killian Senior High School – which his mother attended long ago as part of its first integrated class – before going on to pursue a journalism degree at Howard University. His end goal was telling the stories of those who often went unheard.

“I wanted to bring my talent as a student editor back to Miami and use it specifically to uplift the Black community here,” said former reporter Smith, who earlier in his career covered housing issues, displacement and politics for The Miami Times.

“After a while, I felt like the powers that be weren’t listening or acting on my reporting,” he said. “In my research, I saw that most of us Black people lived in the unincorporated areas. And who is the government for the unincorporated areas? Miami-Dade County. The county has a lot of power to pass laws and create programs to improve the lives of Black people.”

Smith then turned to county government, working first as an aide for Miami-Dade’s first Black county commissioner, Barbara Carey-Shuler, and District 2 Commissioner Jean Monestime before becoming a legislative analyst in the commission’s auditor office after pursuing an MBA from Florida International University.

Prior to his current role, he worked as then Commissioner Daniella Levine Cava’s legislative director, managing her economic development and affordable housing portfolio.

His office is currently pushing for the completion of a county disparity study, expected to wrap up by 2023, that’s a prerequisite for implementing equity-focused policy and programs.

“At the end of the day,” said Smith, “those of us who have the privilege to have these government jobs, our duty is to serve and to solve the problems that our residents come to us with.”